South of Orlando

Tell me the story of your childhood

Memory is remembering, revisiting pieces of information the brain has stored. Memory shapes the way we return to a place. We associate certain emotions or events with a place based on what we remember. Some memories stand out in our minds as if we only left the place moments ago. Other memories are distant, a fuzzy inkling of a place once known.

There are also institutional memories that are handed down through the generations. These memories play an important role in shaping our traditions and customs. Places are memorialized as one’s childhood home, an alma mater, the site of an engagement, or a family vacation spot. Memories of these places are kept alive through photographs and stories.

These associations based on memory are personal, making a place significant for one person but not necessarily another.

My memories of the house are actually my dad’s. The way my dad talks about the Highland Park house makes me think it is paradise in southern Florida. He describes the carefree days he spent running around the neighborhood, soaking up every minute of the sun after another cold Cleveland winter. My dad and his brother spent their time swimming in the pool, fishing in the lake, and playing shuffleboard in their neighbor's backyard. My mom gently reminds my dad that my grandmother probably felt differently about visiting the house in Highland Park because she still did all the cooking and cleaning and entertaining. But for my dad, that house represents his childhood and no homework.

South Highland Park Drive

The house on Highland Park Drive has been in the family since 1972, but Grandma has been visiting the area since she was four. My great-grandmother passed the house down to my grandma who will one day pass it down to her sons. Each generation must make the decision whether to keep or sell.

The house is nothing special to look at. The paint is peeling from the walls and sides of the house from years of humid Florida summers. The rooms are arranged in a strange configuration after a remodel that turned the back of the house into the front.

There are sixty-eight homes in Highland Park and my grandfather can tell you who lives at each address. He knows whether they are year-rounders or vacationers. He can name all the children and grandchildren in the neighborhood. He points out where the annoying dog that yaps all day lives and his friend who has a pool we can use. He knows all of this information from collecting the trash every Tuesday in his beat-up golf cart that he wields like a tank.

My grandfather is a collector. He mostly collects junk from yard sales. Matchbox cars, monopoly money, road signs. But he is also a collector of memories. His arsenal of stories will keep any visitor entertained for hours. This is a trait he passed along to my father.

About an hour south of Orlando, Highland Park is a small village in Lake Wales, Florida. The town was originally spelled “Wailes” after the man who surveyed the land in the 1880’s. As the legend goes, someone forgot the “I” when they were painting a sign for the new train station. The town has been spelled “Wales” ever since.

In Lake Wales, oranges are king. The headquarters for Florida’s Natural are located in the town. Florida’s Natural proudly proclaims to grow, manufacture, and package all of its products in Central Florida. As the largest employer in the area, Florida’s Natural drives the economy of Lake Wales’ in a state known for its beaches, theme parks, and weird newspaper headlines.

"You can be sure that it’s always 100% Florida and never imported."

- Florida's Natural

When citrus does well, the town does well. My dad remembers a booming city from his childhood. Restaurants and shops thrived with the business citrus agriculture brought to the area. But as we drive through town from the airport, things have changed drastically.

The town fell into rough times with many households relying on the one industry for income. In 2017, Hurricanes Irma and Maria devastated the orange groves. It takes a few seasons for farmers to build up their crops to where they were before the storms.

With the town falling into tough times, my grandparents are debating whether keeping the house is worth it. The value of the family memories is up against the realities of the financial cost.

Time changes places

The house has changed since the last time my dad visited, although the kitchen table where my grandpa does his crossword every morning is the same. The signs of hard times are everywhere. The shuffle boards my dad remembers are long gone. The pier he once fished off as a kid is falling into the lake. The community pool that I swam in as a baby was filled in when the owner of the community could no longer afford to keep it open.

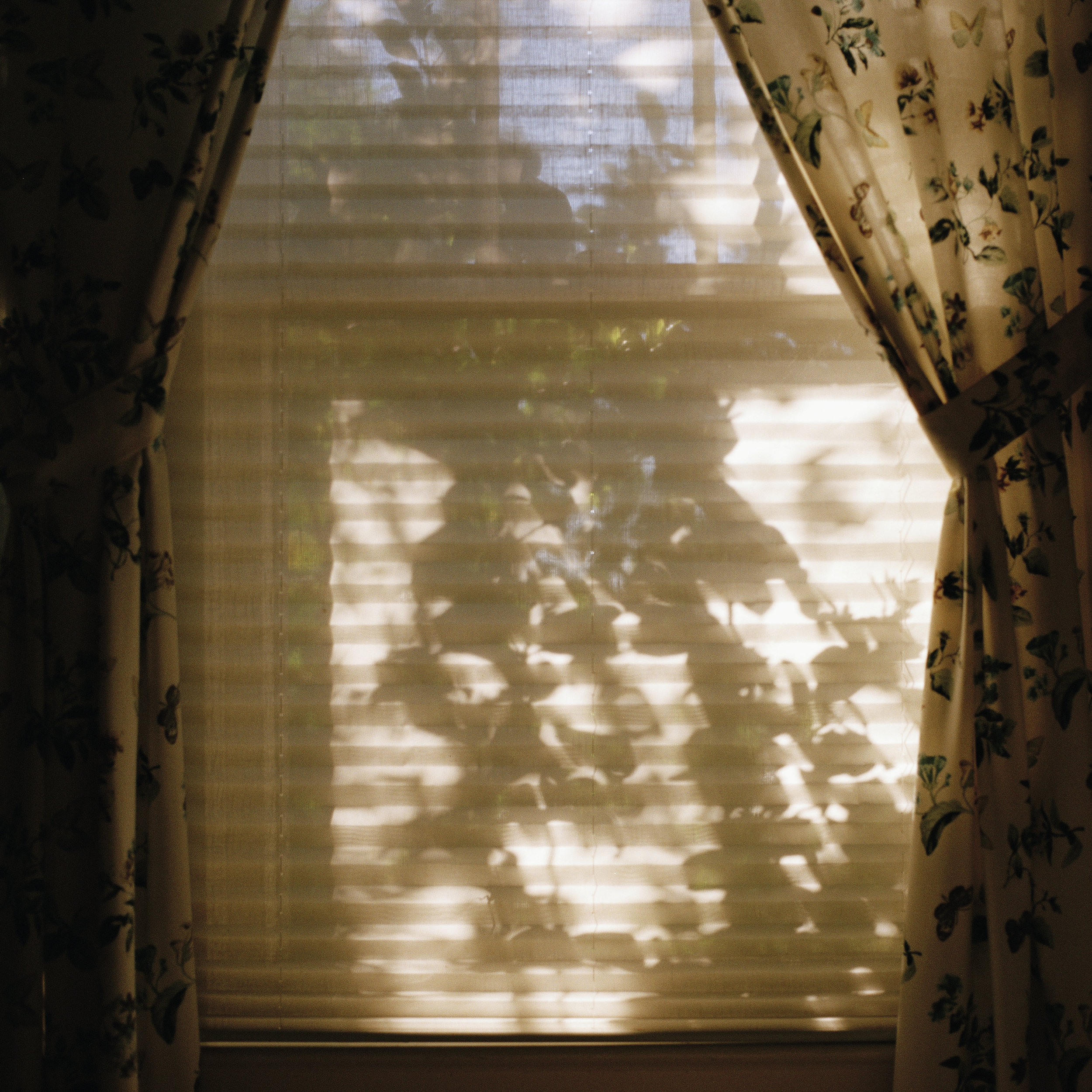

My memories of the Highland Park house are simply that. What I thought I knew through my dad’s stories and my own vague recollections is a strange place in reality. This realization, that the closeness I felt to the place exists in the stories and memories rather than the house itself, is a jarring thought. We remember the things we want to, the good or eventful times, and forget the details that make up a place. Of course, those details also change overtime. A floral pattern replaces the plain yellow curtains I remember. But more than the details, the larger picture seems even more distant up close than it did back home in North Carolina.

Places based on memories fail us as time goes on and the details become unrecognizable. The closeness I felt to the place is due to the people and history of the house rather than the physical location. It's a connection to great grandparents I never met and a time before I was born.

Using the light

The way I chose to photograph this place is important in understanding how I approached this place. I used a Hasselblad medium format film camera, which tells you a couple of important things about my methodology.

Using film, I had no way to know if the photographs would turn out how I wanted. There is no way to review the photographs, change my camera settings, and then adjust for the next photo. Each time I pressed the shutter, I silently hoped that it would turn out how I imagined it in my head. Sometimes the film does not advance all the way and part of two images end up overlapping. These unexpected surprises are part of the magic of film. The decision to use film mirrors the memories this project seeks to explore, fleeting moments captured but unable to fully return to that specific moment in time.

Film is an expensive form of photography in terms of buying the film and having it developed, but also in terms of time. The process of turning a negative into a positive and then editing out all the scratches that inevitably end up on the film takes time. This forces the photographer to get personal with the photos, examining every inch of the image for tiny specks of dust or defective pieces of emulsion that did not work as it was supposed to. Examining every inch of film is akin to examining the memories we thought were truths.

The Hasselblad presents a unique way of viewing subjects because the viewfinder is on top of the camera. The photographer looks down through the lens instead of straight on towards the subject. The mirrors in the camera present the image as backwards, which makes framing tricky when trying to figure out whether to move left or right. Having shot with several different types of film and digital cameras, I can say that this method of looking down into the lens is the most intimate approach. The focus is finicky and requires a precise eye but is worth it in the end.

Ultimately, the practice of photography is the practice of capturing light. It is up to each individual photographer to use that light in a specific way in order to capture a subject or a feeling. As I struggled to connect to a place that was close in my mind, I employed the camera as a tool for framing the space and gaining a new perspective on the memories I was trying to capture.